In the last decade, the intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Materials Science has generated a wave of unprecedented optimism. Headlines frequently announce that deep learning models have discovered millions of new stable crystals, promising better batteries, more efficient solar cells, and room-temperature superconductors. On paper, these models are triumphs of computation, boasting high accuracy scores and rigorous logical consistency.

However, a quiet frustration is brewing in wet labs around the world. While an AI algorithm can hallucinate a crystal structure in milliseconds, synthesizing that material in a furnace can take months—if it happens at all. This disconnect, known as the "synthesis gap," reveals a critical limitation in traditional material discovery: predicting a material exists is fundamentally different from knowing how to make it.

The Digital Alchemist

The quest to discover new materials has traditionally been a game of intuition and serendipity. For centuries, chemists acted as explorers navigating an infinite ocean, mixing elements in crucibles and hoping for a favorable reaction. While this trial-and-error approach gave us bronze, steel, and silicon semiconductors, it is agonizingly slow. The number of possible combinations of elements in the periodic table exceeds the number of atoms in the observable universe, a vast expanse known as "chemical space." To navigate this space efficiently, modern science has turned to a new navigator: Artificial Intelligence.

The fundamental premise of AI in materials science is the replacement of expensive physical experiments—and even expensive physics simulations—with rapid statistical approximations. Before the rise of deep learning, the gold standard for predicting a material's properties was Density Functional Theory (DFT). DFT solves the Schrödinger equation to calculate the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons within a crystal. While highly accurate, it is computationally exhausting; a single calculation for a complex crystal can occupy a supercomputer for days. AI models, by contrast, treat this physics simulation as a pattern recognition problem. By training on databases containing hundreds of thousands of previously calculated DFT results, the AI learns to predict the outcome without actually doing the quantum math.

To make these predictions, the AI must first perceive the material in a way a computer can process. Since an algorithm cannot "see" a crystal in the traditional sense, scientists convert the atomic structure into a mathematical fingerprint, known as a descriptor or feature vector. This vector encodes essential chemical information, such as the electronegativity of the elements involved, their atomic radii, and the geometry of how the atoms are packed together. For instance, a Graph Neural Network (GNN) views atoms as nodes and chemical bonds as edges, passing information between neighbors to understand the local chemical environment. Once the material is digitized into these vectors, the model searches for non-linear correlations between these features and a specific target property.

The most critical property these models predict is formation energy. This metric is the arbiter of stability. It represents the difference in energy between a compound and its constituent elements in their pure states. Nature inherently prefers low-energy states; water flows downhill, and atoms arrange themselves to minimize internal tension. Therefore, if an AI model predicts that a specific arrangement of atoms has a highly negative formation energy, it suggests that the material is thermodynamically stable. It implies that if you were to put these atoms together, they would naturally want to stick in that configuration rather than falling apart.

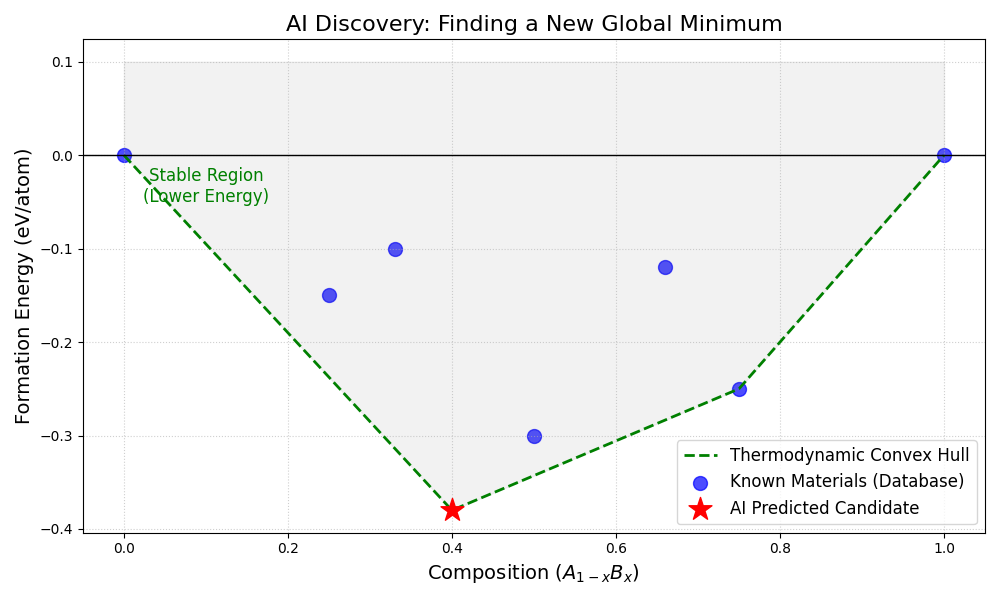

This concept is best visualized through the "Convex Hull." Imagine a plot where the horizontal axis represents the ratio of two elements mixing together, and the vertical axis represents energy. The known stable materials form a boundary line at the bottom of the graph. Any material that falls above this line is unstable and will decompose. Any material that falls on or below this line is deemed stable. The primary triumph of modern AI models is their ability to scan millions of theoretical candidates and identify the rare few that puncture this hull, signaling a brand-new, stable material waiting to be born.

Figure 1.1: A visualization of the Convex Hull construction. The blue dots represent materials already known to science. The green dashed line represents the current limit of stability; nature "rolls down" to this line. The red star represents an AI prediction. Because the red star possesses a lower formation energy than the combination of materials around it, the algorithm logically concludes that this new material is thermodynamically stable and should be synthesizable.

The logic of the Convex Hull discussed previously is mathematically sound, yet it hides a significant simplification that renders many AI predictions physically unattainable. The vast majority of the training data used for these models—databases like the Materials Project or OQMD—are derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations performed at zero Kelvin. At absolute zero, atoms stop vibrating, and entropy ceases to exist. In this frozen digital vacuum, complex, precarious crystal structures can appear perfectly stable because there is no thermal energy to shake them apart.

Real-world synthesis, however, occurs in furnaces blazing at 1,000 degrees Celsius or more. In these conditions, entropy becomes a dominant force. A crystal structure that sits comfortably at the bottom of an energy well at zero Kelvin may become thermodynamically unfavorable when heat is applied. The vibrating atoms might prefer to disintegrate into a disordered, amorphous mess rather than hold the complex shape predicted by the AI. The algorithm sees a sturdy architecture; the chemist sees a sandcastle trying to survive a hurricane.

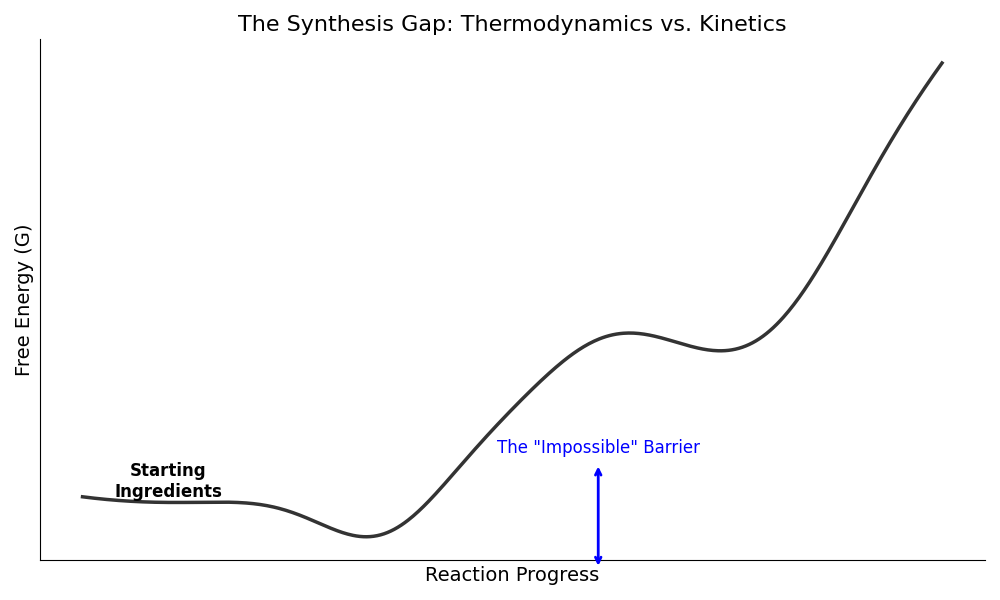

Furthermore, even if the material remains stable at high temperatures, the AI often fails to account for the "pathway" required to build it. This is the distinction between thermodynamics and kinetics. Thermodynamics tells us which state is the most stable (the destination), while kinetics dictates how fast the reaction happens and what barriers lie in the way (the journey).

For a chemical reaction to occur, atoms must overcome an energy barrier, known as activation energy. The AI might identify a "Super Material" that sits in a very deep energy valley, representing a perfect, stable state. However, if the mountain range surrounding that valley is insurmountable—meaning the activation energy is too high—the atoms will never be able to climb over and settle into the desired structure. Instead, they will roll into the first accessible, shallow valley they find. This shallow valley represents a "kinetic byproduct," a common, boring material that forms quickly and easily, ruining the experiment. The AI predicts the diamond; the lab produces the graphite.

The following Python code illustrates this "Kinetic Trap." It shows an energy landscape where the AI identifies the global minimum (the best material), but the reaction gets stuck in a local minimum because the barrier to reach the prize is too high.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# Define the reaction coordinate (x-axis)

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 500)

# Create a synthetic energy landscape using a combination of Gaussian functions

# 1. Starting material (Reactants) at x=1

# 2. Kinetic Trap (Unwanted byproduct) at x=3.5 (Shallow well, low barrier)

# 3. Thermodynamic Product (AI Prediction) at x=8 (Deep well, high barrier)

y = (0.5 * (x - 1)**2) # Base parabola to create a "container"

y -= 6 * np.exp(-0.5 * (x - 3.5)**2 / 0.5) # The Kinetic Trap (Intermediate)

y -= 9 * np.exp(-0.5 * (x - 8.0)**2 / 0.8) # The AI Prediction (Global Min)

y += 3 * np.exp(-0.5 * (x - 6.0)**2 / 0.5) # The High Barrier

# Plotting

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(x, y, color='#333333', linewidth=2.5)

# Annotate Reactants

plt.text(1, 0.5, 'Starting\nIngredients', ha='center', fontsize=12, fontweight='bold')

# Annotate the Kinetic Trap

plt.annotate('The Kinetic Trap\n(What actually forms)',

xy=(3.5, -6), xytext=(3.5, -2),

arrowprops=dict(facecolor='red', shrink=0.05),

ha='center', color='red', fontsize=11)

# Annotate the AI Prediction

plt.annotate('AI Predicted Material\n(Thermodynamically Stable)',

xy=(8.0, -9), xytext=(8.0, -5),

arrowprops=dict(facecolor='green', shrink=0.05),

ha='center', color='green', fontsize=11)

# Annotate the Barrier

plt.text(6.0, 4.5, 'The "Impossible" Barrier', ha='center', fontsize=12, color='blue')

plt.annotate('', xy=(6.0, 3.5), xytext=(6.0, -6),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='<->', color='blue', lw=2))

# Styling

plt.title('The Synthesis Gap: Thermodynamics vs. Kinetics', fontsize=16)

plt.ylabel('Free Energy (G)', fontsize=14)

plt.xlabel('Reaction Progress', fontsize=14)

plt.yticks([]) # Remove arbitrary y-numbers for conceptual clarity

plt.xticks([]) # Remove x-numbers

plt.grid(False)

# Remove top and right spines

ax = plt.gca()

ax.spines['top'].set_visible(False)

ax.spines['right'].set_visible(False)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Figure 1.2: The Energy Landscape. The AI successfully identifies the green well (the Global Minimum) as the most stable state. However, it ignores the blue barrier. In a real experiment, the reactants (ingredients) do not have enough energy to climb the high barrier. Instead, they fall into the red well—a local minimum. This results in an unwanted byproduct rather than the "perfect" material the AI promised.

The Performance Paradox

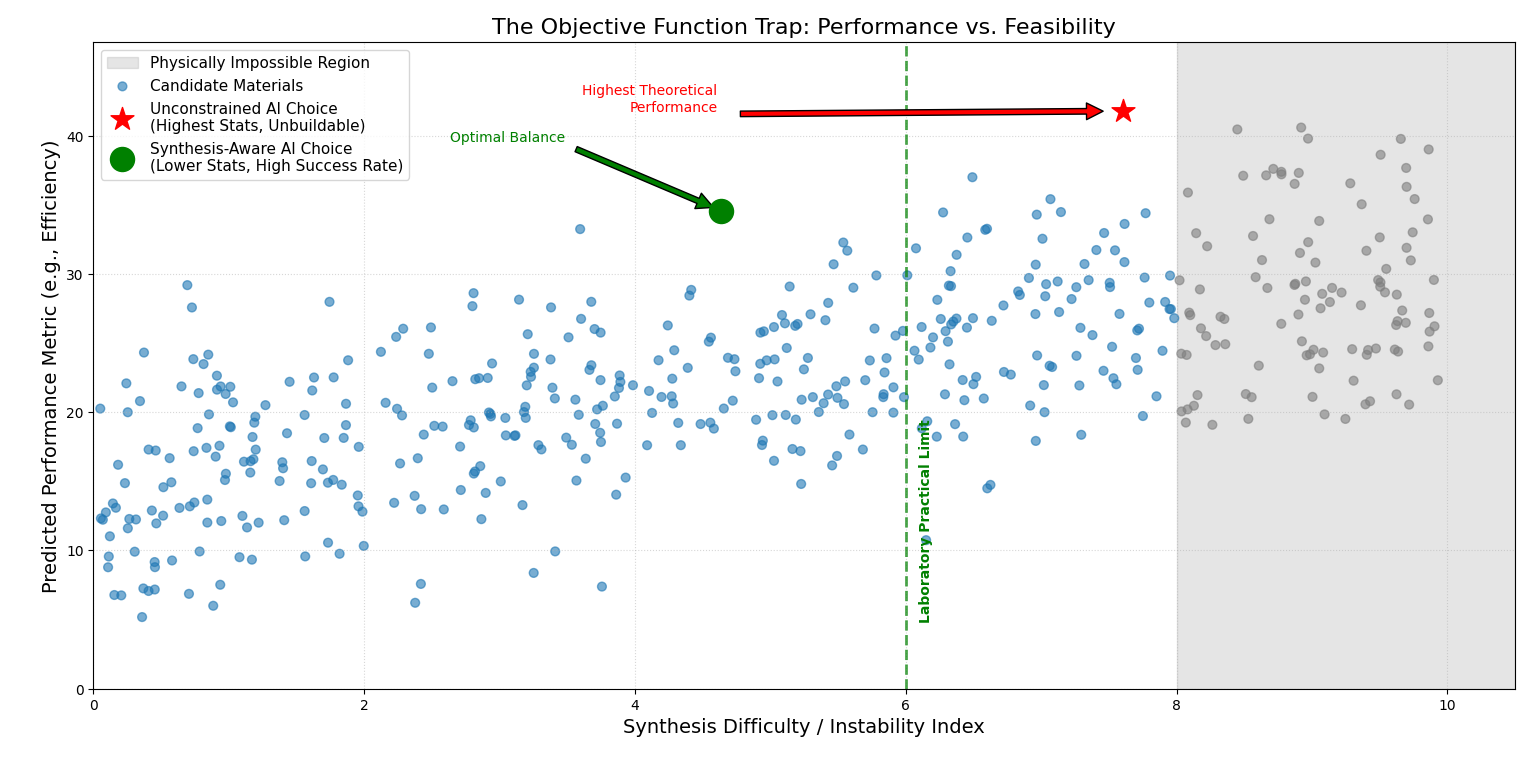

The disconnect between digital prediction and physical reality is not merely a byproduct of missing data; it is a structural flaw in how we define success for artificial intelligence. In machine learning, an algorithm’s behavior is governed by its "objective function" or "loss function"—a mathematical rule that tells the model what to value and what to ignore. When researchers design AI to discover new materials, the objective function is almost invariably tied to a theoretical performance metric, such as maximizing battery voltage, electron mobility, or thermal conductivity. The AI, acting as a ruthless and literal interpreter of these instructions, scours the chemical universe for atomic configurations that satisfy this mathematical goal, completely agnostic to the physical struggle of creation.

This creates a dangerous dynamic where the AI learns to exploit the "edge cases" of physics. In the vastness of chemical space, extreme properties often arise from extreme structures—configurations that are chemically strained, thermodynamically precarious, or hyper-complex. A neural network tasked solely with maximizing hardness, for instance, might converge on a crystal lattice that is incredibly dense and theoretically harder than diamond. The mathematics of the simulation permit this structure to exist in a vacuum. However, the model is blind to the fact that creating such a lattice might require pressures found only in planetary cores, or that the arrangement is so unstable it would detonate upon contact with the moisture in a lab's air. The AI has optimized for the destination while ignoring the impassability of the road.

This issue is compounded when we consider the difference between "Generative Exploration" and "Constrained Screening." A standard generative model, similar to those used to create art or text, is rewarded for novelty and high scores on the target metric. It behaves like an architect sketching a skyscraper that defies gravity—beautiful, record-breaking, but unbuildable. Because "synthesizability" is a difficult concept to quantify—it has no single number like "voltage" or "mass"—it is rarely included in the objective function. Consequently, the AI drifts toward "Unobtainium," a class of materials that exist only as data points on a server, boasting theoretical efficiencies that can never be realized because their atomic bonds are too weak to survive the thermal chaos of a real-world furnace.

To fix this, the field must move toward Multi-Objective Optimization. In this approach, the AI is not just asked to maximize performance; it is simultaneously penalized for complexity or predicted instability. This forces the model to make trade-offs, accepting a slight reduction in theoretical performance to gain a massive increase in the probability of successful synthesis. Until we change the question we ask the AI—from "What is the best material?" to "What is the best buildable material?"—we will continue to generate accurate predictions of impossible things.

Figure 2.1: The Divergence of Outcomes. The scatter plot represents thousands of potential materials. The red star shows the material selected by a traditional AI model: it has the highest theoretical performance but sits deep within the "Impossible Region" of synthesis difficulty (high instability). The green circle represents a material selected by a Synthesis-Aware model. It accepts a lower performance score to ensure the material sits within the "Laboratory Practical Limit," ensuring that the prediction can actually be converted into a physical reality.

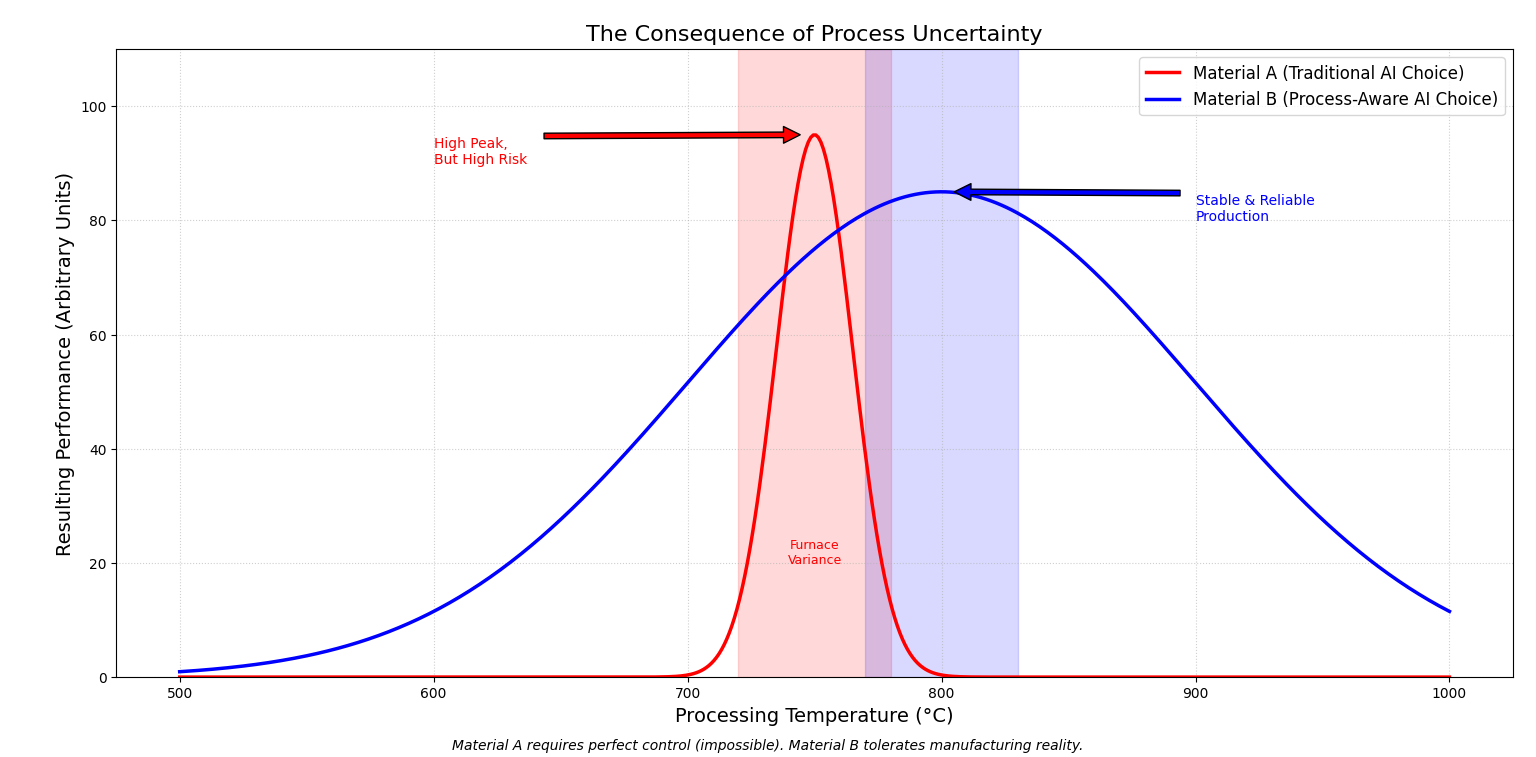

The fatal flaw in traditional material prediction lies in treating a chemical formula as a deterministic destiny. In reality, materials science bears a striking resemblance to biology. A genome (DNA) dictates the potential of an organism, but the environment determines how that potential is expressed—a concept known as the phenotype. Two genetically identical seeds planted in different soils with different watering schedules will grow into vastly different plants. Similarly, a chemical composition—let's call it the "material genotype"—does not guarantee a specific outcome. The "material phenotype," which is the actual physical sample with its conductivity, hardness, and defects, is the product of its processing history.

Current AI models operate like a biologist who only looks at DNA sequences and ignores the environment. They predict that a specific arrangement of atoms will yield a high-performance superconductor, assuming a perfect, idealized existence. However, they fail to account for the chaotic "environmental" factors of synthesis: the slight fluctuation in furnace temperature, the microscopic impurities in the precursor powder, or the humidity in the lab on a rainy Tuesday. These uncertainties are not noise; they are the governing dynamics of reality. A material that requires 0.01% precision in cooling rate to form correctly is effectively useless in an industrial setting, yet a static AI model sees it as a perfect candidate. By ignoring the stochastic nature of synthesis, we are predicting the equivalent of a tropical orchid but planting it in a desert, wondering why it fails to bloom.

To bridge this gap, we must fundamentally alter the data architecture of materials discovery. It is no longer sufficient for AI to learn from static databases of theoretical crystal structures. Instead, the AI must plug directly into the "nervous system" of the laboratory itself. We need a continuous, unbreakable data chain that captures the entire lifecycle of a material, linking the raw ingredients to the final performance metrics.

In this integrated approach, the AI does not just read the chemical formula. It reads the log files from the ball mill that mixed the powders, the thermal couples inside the sintering furnace, and the pressure sensors on the press. It ingests the "metadata of failure" and the "telemetry of success." By analyzing this stream of process data, the AI learns to correlate specific synthesis conditions with structural outcomes. It moves from asking "What is the stable structure?" to asking "What is the processing window that reliably produces this structure?" This shift transforms the AI from a theoretical physicist into a seasoned process engineer, capable of identifying materials that are not just theoretically excellent, but robust enough to survive the uncertainties of the real world.

Figure 2.2: The Robustness Trade-off. The red curve represents a material selected by traditional AI: it has a high theoretical maximum, but if the manufacturing temperature drifts even slightly (represented by the shaded red zone), the performance collapses. The blue curve represents a material selected by an AI with access to production data. It recognizes that while the peak is lower, the broad "plateau" ensures consistent quality despite real-world fluctuations in the manufacturing process.

The Fully Automated AI Laboratory

Once we acknowledge that data must flow continuously from the furnace to the algorithm, the next logical step is to remove the slowest link in that chain: the human operator. The integration of AI with hardware has given birth to the concept of the "Self-Driving Laboratory," a facility where the feedback loop between prediction, synthesis, and characterization is closed by robotic automation. In these facilities, the AI does not merely suggest a recipe; it executes it.

A fully automated AI laboratory functions as a closed ecosystem of discovery. An algorithmic "brain" generates a hypothesis—for example, that adding 2% magnesium to a mixture will improve stability. It transmits this instruction to a robotic arm, which precisely weighs the powder, loads the crucible, and places it into a furnace. Once the synthesis is complete, automated characterization tools, such as X-ray diffractometers or electron microscopes, analyze the sample. Crucially, the data from this experiment—whether it is a glowing success or a dismal failure—is instantly fed back into the central model. The AI updates its understanding of the chemical space in real-time, learning from the immediate consequences of its own decisions.

This creates a profound shift in the speed of innovation. A human researcher might complete one or two optimization cycles in a week; a self-driving lab can perform dozens or even hundreds in a day. More importantly, the robot eliminates the "tacit knowledge" problem. When a human scientist performs an experiment, they often make subtle, unrecorded adjustments based on intuition. A robot, however, records every parameter with exacting precision. This exhaustive data capture allows the AI to detect subtle patterns—such as the correlation between humidity levels at 3:00 AM and crystal defect rates—that a human would never notice. By automating the physical execution, we convert the messy art of synthesis into a structured data stream, finally giving the AI the grounded reality it needs to make predictions that actually work.

Ref.

- Butler, K.T., Davies, D.W., Cartwright, H. et al. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 559, 547–555 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0337-2

- Raccuglia, P., Elbert, K., Adler, P. et al. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature 533, 73–76 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17439

- Merchant, A., Batzner, S., Schoenholz, S.S. et al. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 624, 80–85 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06735-9

作者:GARFIELDTOM

邮箱:coolerxde@gt.ac.cn